The Angular “Template Context” is a practically useful mental model, which once internalized, will be your main guide on the journey to build the best possible Angular applications!

Foreword

This article is pretty long, but don’t worry, it’s not because Angular is just soooo damn complicated… It’s because we’re painting a very board picture and looking at it from all the imaginable angles so that in the end you will end up with 100% full understanding of the topic!

In theory, you could just search for the heading saying “Template context” , but I would strongly advise to check the whole thing 😉

TLDR; In Angular, template related things declarables ( components, directives and pipes ) that use each other in their templates have to be part of THE SAME “template context” which is defined by @NgModule (or the component itself when using new stand-alone components SAC approach), application then usually has multiple “origin template contexts”, namely the eager ( root ) one and then for every lazy loaded @NgModule. On the other hand, every SAC defines its own “template context” in full.

Hey folks!

Recently there have been a great new surge of Angular buzz and for a good reason!

The new exciting times for Angular are upon us!

The Angular 13 finally removed old rendering engine called ViewEngine and was therefore the first IVY only release.

With this monstrous task being out of the way, Angular team can now focus on delivering new epic features like fully typed reactive forms, improvements for developer experience and the evolution of the framework itself!

The main effort on this field was embodied by the initiative to allow us to develop Angular applications without @NgModules and use the new stand-alone components ( SAC ) approach introduced in developer preview in Angular 14.

With Angular 15 released just now ( 17.11.2022 ) the SACs just came out of developer preview and became a development approach with first class support from Angular CLI and other parts of the framework.

Angular Stand-alone components represent next big step in evolution of the framework and therefore may trigger past fears of large breaking change similar to Angular JS to Angular

Thankfully, this is not the case at all!

More so, we’re going to discover that both @NgModules based approach and the SAC approach share common underlying reality which remains in place unchanged! Because of this, it serves as a proof to the contrary, Angular was, is and stays very stable and dependable piece of technology.

I hope that this caught your attention and made you curious about that “common underlying reality” and that’s exactly what we’re going to explore in this article!

But first, we have to extend our view and paint a larger picture so that it all makes sense in the end, let’s start with…

Mental models

A mental model is an explanation of someone’s thought process about how something works in the real world. It is a representation of the surrounding world, the relationships between its various parts and a person’s intuitive perception about their own acts and their consequences. Mental models can help shape behavior and set an approach to solving problems ( similar to a personal algorithm ) and doing tasks Wikipedia

The official definition gives us a hint about how this could be useful but let’s explore it more from a developer perspective using the concepts we’re all familiar with.

Ignoring all the philosophical considerations and focusing on creating a useful metaphor will allow us to say that in general, our brains are similar to a computer running a software ( mind ) and that software is programmable ( learning ).

Example: “A variable”

A useful piece of such “mind software”, can be named a “mental model”. An example of such model which is most likely very familiar to all of us can be “a variable” which then usually can be described like the following…

- variable can store a value ( typed / untyped / which type (based on language) )

- variable can be reassigned with another value ( or not if constant )

- variable is accessible from some places and not from the others ( eg scope, property of class, … )

- variable can be referenced to use its value for some computation

- the list could go on, and be nuanced based on specific language, use case…

Having such mental model allows us to use that concept of “variable” when trying to achieve desired goal when writing code to implement some feature.

We all posses myriads of mental models which we use seamlessly, often without noticing, on day-to-day basis!

Mental models are often combined and build upon each other, for example let’s take “variable” and “array” where arrays are often stored in variables but come with their own mental model of having multiple values and ways to process these values like map or filter and so on…

Limited mental models

It is often the case that our mental model is only very basic, just enough to get things done and that’s fine. In the end, all that matter is that we achieve desired outcome which might very well be possible with limited understanding of the subject.

For example, we would be able to use variables even if we were oblivious to the concept of typing system of a language like TypeScript. After all, we could just type everything as any and still create an useful application which is loved by the users!

In that case we would be applying our limited mental model and achieving outcomes but those outcomes would be suboptimal and could cause us troubles in the future, for example when we want to extend our untyped application or onboard another colleague to work on the same code base.

Based on my personal experience from developing, consulting and teaching Angular in enterprise organizations, developers often poses only a limited version of the “template context” mental model. Similar to previous example, while the applications are delivered successfully, it is often in suboptimal state which tends to limit their evolution and balloon the costs of maintenance as the business requirements change!

Limited version of the “template context” mental model often leads to Angular applications in suboptimal state which tends to hamper their evolution and balloon the costs of maintenance!

Templates

Now it’s time to get more practical. In Angular, when we want to display something, we know we have to use a component and especially component template where we are using declarative approach to define:

- what should be displayed, eg

<h1>Hello world</h1> - how it should change, eg

<p>{{ user.name }}</p> - how to handle interaction, eg

<button (click)="save()">Save</button>

This is in stark contrast to long forgotten world of imperative template rendering with approaches like setting value of

.innerHTMLwhenever we needed to change what was displayed.

Then an example of component could be something like this…

@Component({

selector: 'my-org-user-item',

template: `

<mat-card>

<mat-card-header>

<mat-card-title>{{ user.name }} {{ user.surname }}</mat-card-title>

<mat-card-subtitle>{{ user.role }}</mat-card-subtitle>

</mat-card-header>

<mat-card-actions align="end">

<button mat-button (click)="edit()">Edit</button>

<button mat-button (click)="remove()">Remove</button>

</mat-card-actions>

</mat-card>

`,

})

export class UserItemComponent {

@Input() user: User;

edit() {

/* ... */

}

remove() {

/* ... */

}

}

Angular allows to extract template in the separate HTML file which is then referenced with

templateUrlproperty in the@Component()decorator but this is a matter of subjective preference.

Let’s focus on the template…

<mat-card>

<mat-card-header>

<mat-card-title>{{user.name}} {{user.surname}}</mat-card-title>

<mat-card-subtitle>

<mat-icon [svgIcon]="user.role"></mat-icon>

{{user.role}}, {{user.lastLoggedIn | date }}

</mat-card-subtitle>

</mat-card-header>

<mat-card-actions align="end">

<button mat-button (click)="edit()">Edit</button>

<button mat-button (click)="remove()">Remove</button>

</mat-card-actions>

</mat-card>

What is going on here? We can see some well known stuff like standard HTML <button> but also more peculiar elements like <mat-card> or <mat-icon>.

More so, we see that the <button> has an attribute which seems to follow similar naming convention as the other elements, namely mat-button and then there is this one more thing, the | date pipe is used to transform the value of lastLoggedIn property of the user object.

Based on this we can say that the Angular component template can use following entities:

- standard HTML elements, eg <button>, …

- other Angular components, eg

<mat-card><mat-icon>, … - Angular directives, eg

mat-button - Angular pipes, eg

| dateor| json

Every Angular component can use all the standard HTML elements in its template out of the box

But what about other Angular components, directives and pipes?

Declarables

In Angular, everything which has something to do with template ( components, directives and pipes ), can be called a declarable because all of them need to be declared (part of the declarations:[ ] array in exactly single parent @NgModule (or be declared as a standalone component, directive or pipe…

If we just wrote this component and its template without any other setup we would get error like the following for all the Angular based components ( and other declarables ) !

Error: user-item.component.html:1:1 - error NG8001: 'mat-card' is not a known element: 1. If 'mat-card' is an Angular component, then verify that it is part of this module. 2. If 'mat-card' is a Web Component then add 'CUSTOM_ELEMENTS_SCHEMA' to the '`@NgModule`.schemas' of this component to suppress this message.

Let’s ignore the Web Component use case for now and focus purely on Angular. The error gives us a main hint that in case the is an Angular component, it needs to be part of “this module”.

The story would go along the similar lines when if we used new Angular Stand-alone components approach, let’s have a look…

Error: user-item.component.html:1:1 - error NG8001: 'mat-card' is not a known element: 1. If 'mat-card' is an Angular component, then verify that it is included in the '@Component.imports' of this component. 2. If 'mat-card' is a Web Component then add 'CUSTOM_ELEMENTS_SCHEMA' to the '@Component.schemas' of this component to suppress this message.

As we can see, the error is basically the same, pointing out to the fact that if the is an Angular component, it needs to be part of the imports of “this component”.

The error we get when we use another Angular component in the template of our original Angular component works exactly the same with both NgModules and new Angular Stand-alone components which demonstrates that the “template context” model will stay useful and relevant for the years to come!

Besides that, this concept will work the same way for both directives and pipes. We would get an error in case we want to use them, but they are not “a part” of the module or the stand-alone component!

Let’s take another small detour before we arrive to the final destination and discuss all the nitty-gritty of the “template context” with examples and best practices for a real world use when developing Angular applications and discuss the context on its own…

Context

Context can be a text in which a word appears and which helps ascertain its meaning. Without any context, we could not tell if the “dish” refers to the food ( eg roasted chicken ), or the thing you eat it on ( eg plate ).

In life, we hear about many contexts and contextual information or information which needs to be understood within the boundaries of some context else would seem out of place or make no sense at all…

On a more practical side, context in software development fortunately has a more narrow meaning!

In general, when we talk about context, we mean things which belong together, are accessible for each other or belong to the same scope.

Great, all the pieces are in place, we now know:

- WHY Angular NgModules vs SAC is upon us, is it a reason to worry, what are the implications?

- HOW Using of templates, Angular components, directives and pipes within each other templates, they need to belong to same module or component else we get error…

- the only thing left is the WHAT, how to work with template contexts to get the best possible Angular applications!

Now it’s time to program your mind by installing a new mental model, the “template context”, but only if you let me! 😅

Template context

Let’s start with something extremely basic, a component which uses one other component in its template…

@Component({

selector: 'my-org-root',

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

}

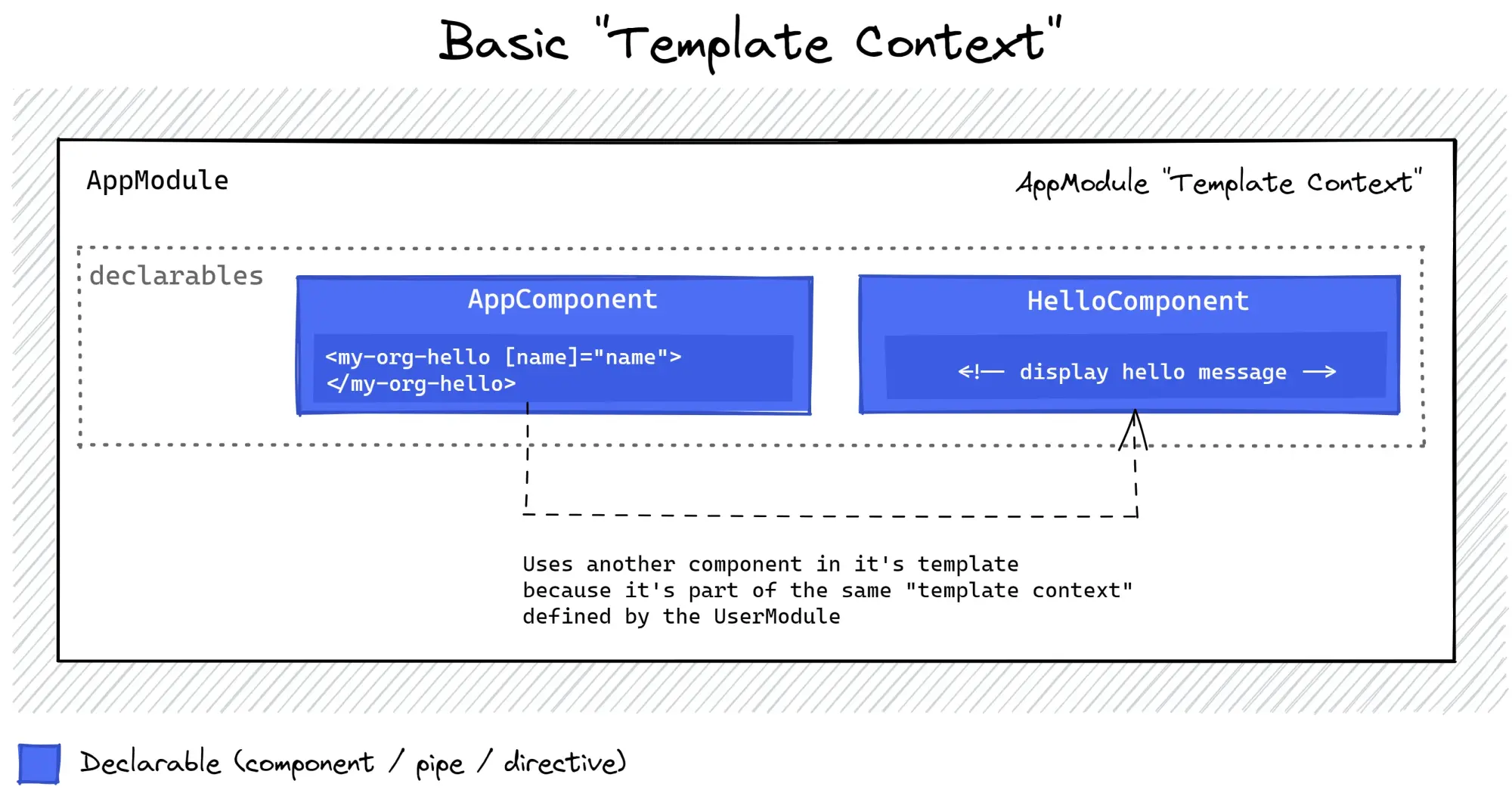

The original NgModule approach

Let’s say our AppComponent belongs to the AppModule which means it is part of that modules declarations: [ ] array.

When using,

@NgModules, a single component always belong to a single module, so it can only be a part of a singledeclarations: [ ]array!

Our initial module could then look something like this…

@NgModule({

declarations: [AppComponent], // declared in exactly one module

imports: [], // let's ignore this for now

bootstrap: [AppComponent], // we have to bootstrap our app

})

export class AppModule {} // our first root template context

If we tried to compile this, we are going to get an error similar to the earlier errors about the my-org-hello not being part of the same “template context” ( Angular module ).

The fix then would be simple, adding that component to the same list of declarations: [ ].

@NgModule({

declarations: [AppComponent, HelloComponent], // <- added HelloComponent

imports: [],

bootstrap: [AppComponent],

})

export class AppModule {}

Great, our application now compiles and works as expected!

Both AppComponent and HelloComponent are part of the same “template context” ( in this case @NgModule ) which means we can use <my-org-hello> in the AppComponent template.

Multiple modules

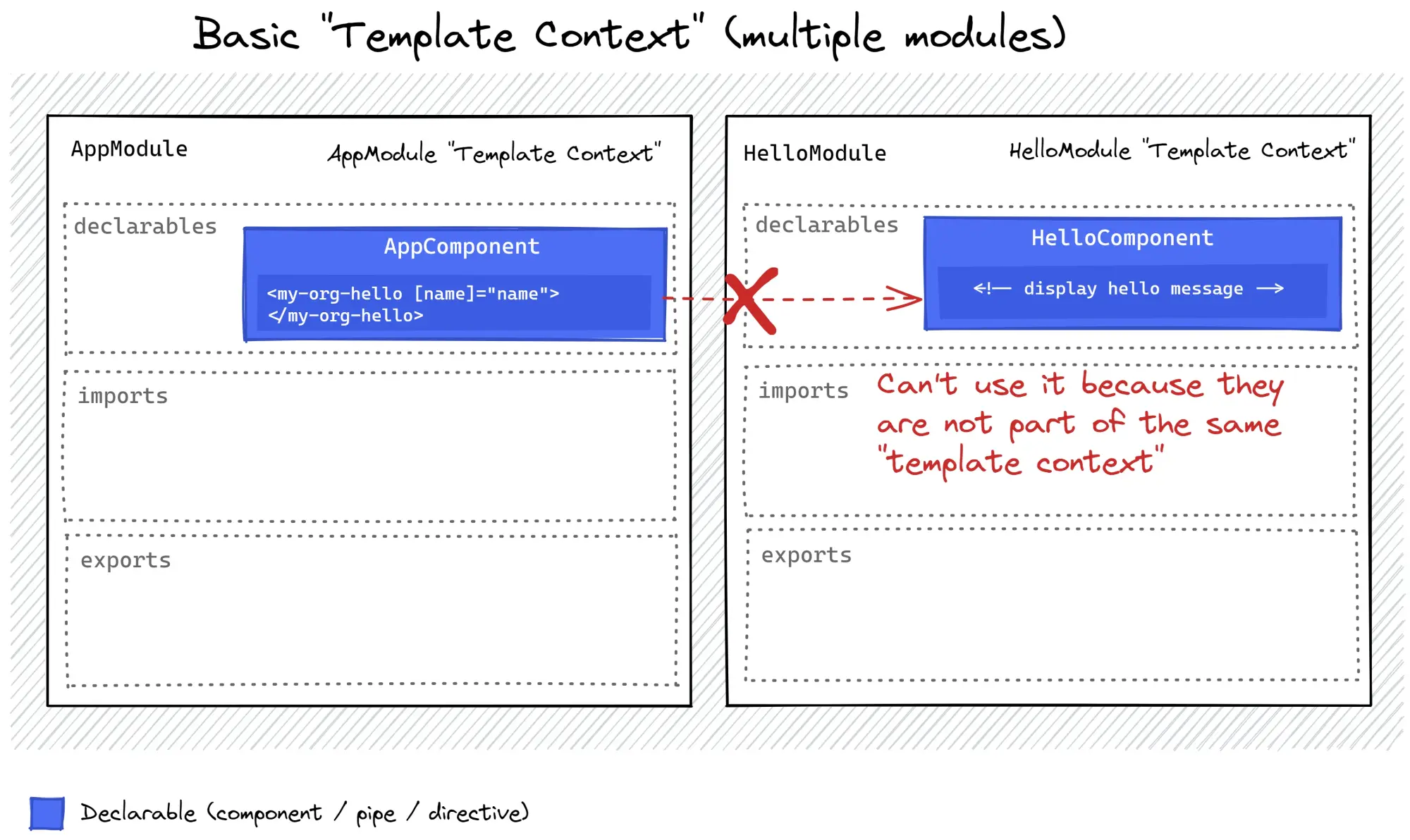

Now let’s expand on our example by moving HelloComponent to another module, let’s call it HelloModule.

@NgModule({

declarations: [HelloComponent], // <- declared in exactly one module

imports: [],

exports: [],

})

export class HelloModule {}

We know Angular components can only be part of a declarations: [ ] array of a single module which means we will have to remove it from the declarations: [ ] of the AppModule so it is no longer part of AppModules “template context”.

As we have learned an @NgModule defines a new “template context” where declarables can use each other in their templates so our HelloComponent now became a part of the new “template context” defined by the HelloModule. This means we have now TWO “template contexts” which are currently separated from each other.

The application will now fail again with the same error as previously about my-org-hello being an unknown element.

Follow me on Twitter because you will get notified about new Angular blog posts and cool frontend stuff!😉

Privacy

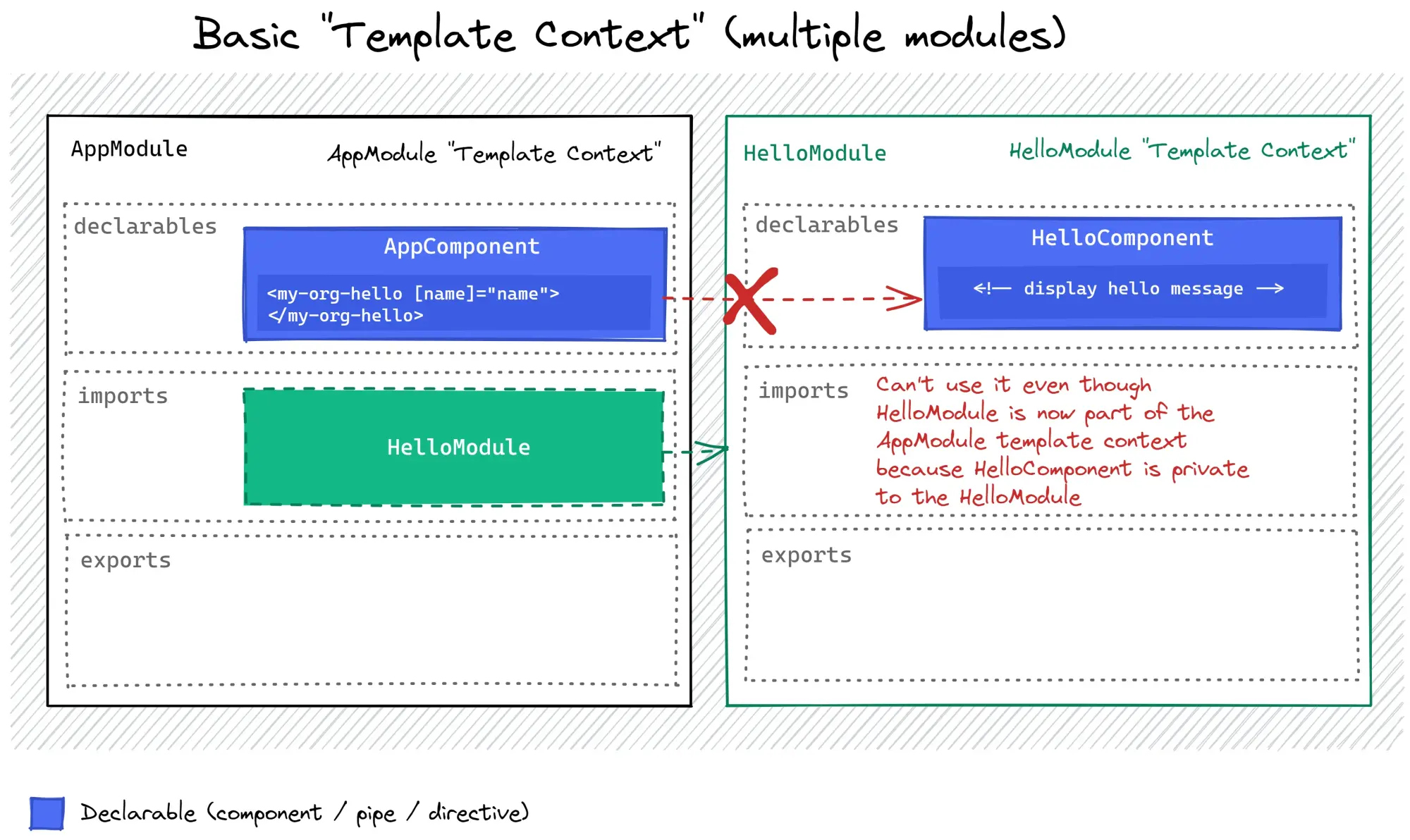

Let’s try to fix it by adding the HelloModule to the imports: [ ] array of the AppModule.

@NgModule({

declarations: [AppComponent], // <- removed HelloComponent

imports: [HelloModule], // <-added HelloModule

bootstrap: [AppComponent],

})

export class AppModule {}

The HelloModule now became part of the AppModule “template context” which sounds good but the application still fails with the same error?!

The reason for that is that the HelloComponent is currently private to the HelloModule “template context” because it’s part of its declarations: [ ] array but NOT part of its exports: [ ] array!

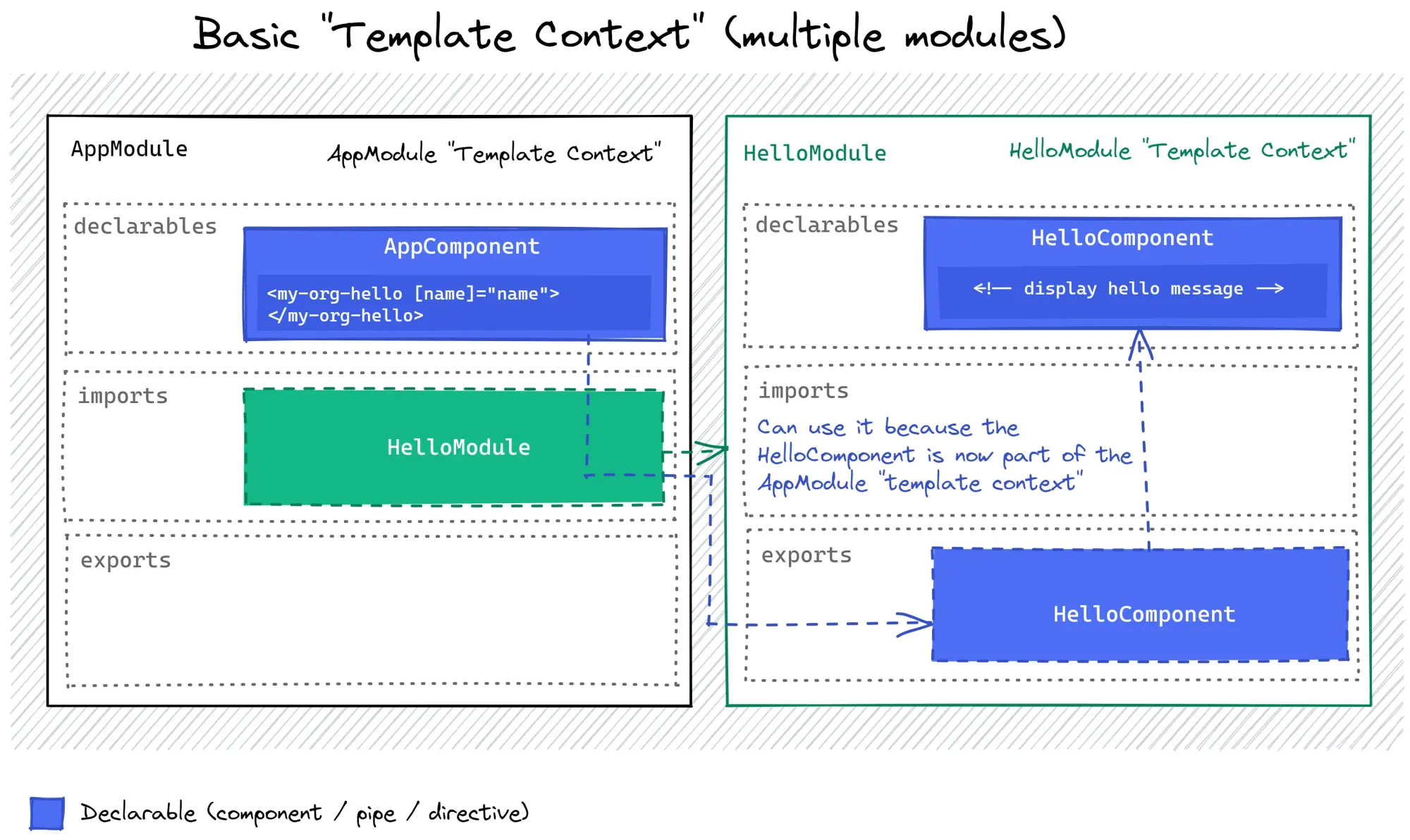

Let’s fix it and see what happens.

@NgModule({

declarations: [HelloComponent], // <- declared in exactly one module

imports: [],

exports: [HelloComponent], // <- added HelloComponent to exports

})

export class HelloModule {}

The application now works again!

Let’s take a step back and break down what is going on:

AppComponentbelongs toAppModule“template context”HelloComponentbelongs toHelloModule“template context”AppComponentwants to useHelloComponentin its template which means that it has to be part of the same “template context” defined byAppModule- To do that we add

HelloModulein theimports: [ ]array of theAppModule( soAppModulehas now access to theHelloModule“template context” ) - Finally, we have to add

HelloComponentto theexports: [ ]array of theHelloModuleelse it will not be accessible from the new biggerAppModule“template context” which now also includesHelloModule

Components which belong to a single “template context” are private to that context unless they are added to the exports: [ ] array!

Single Component Angular Module ( SCAM ) Pattern

Our current HelloModule with only a single HelloComponent which is part of both declarations: [ ] and exports: [ ] represents a well-known pattern in Angular development called Single Component Angular Module or SCAM ( unfortunate abbreviation🤷♂️ ).

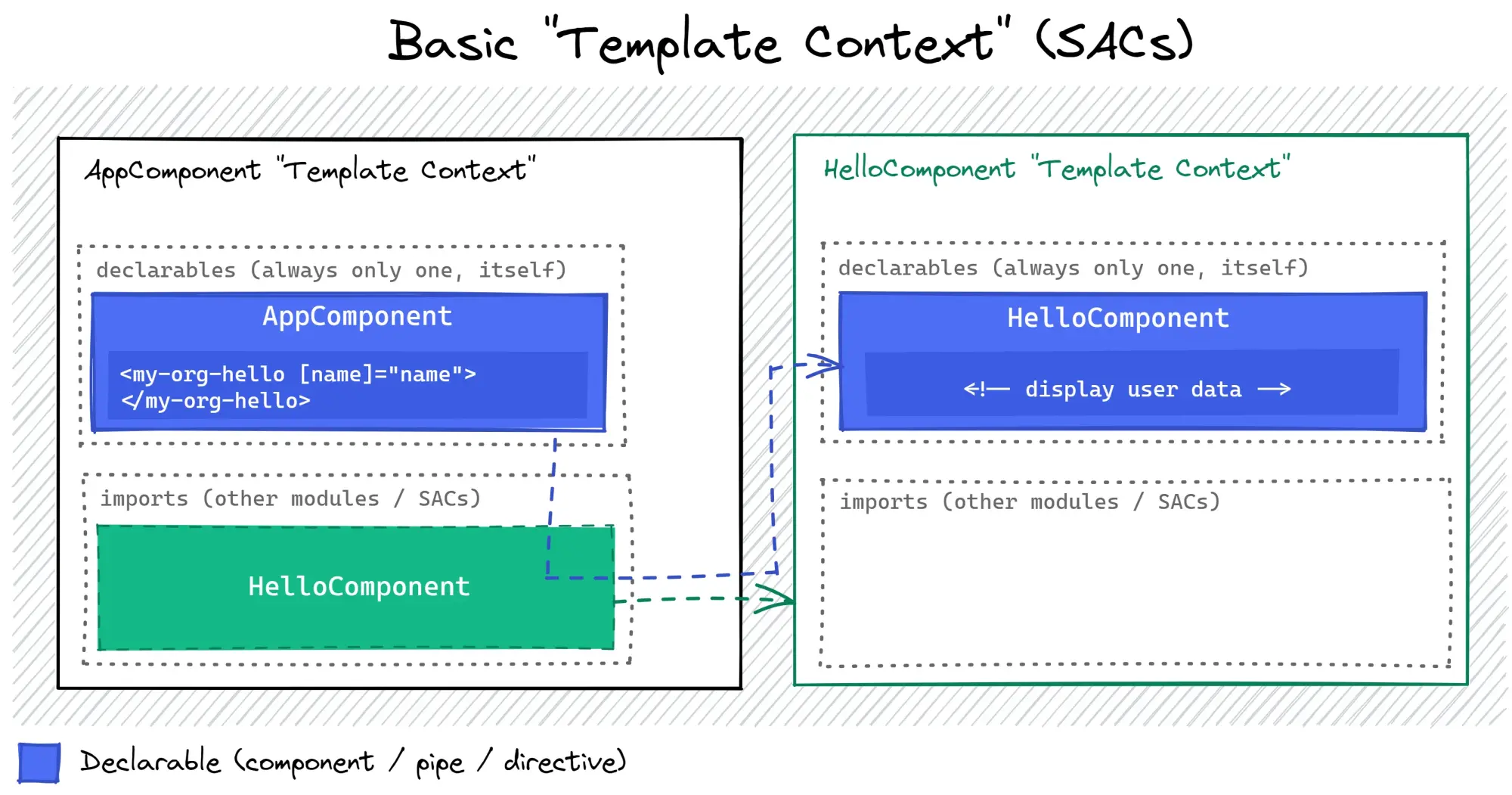

This will be important later on when exploring Stand-alone components based approach because we will see that every SAC behaves exactly as a SCAM!

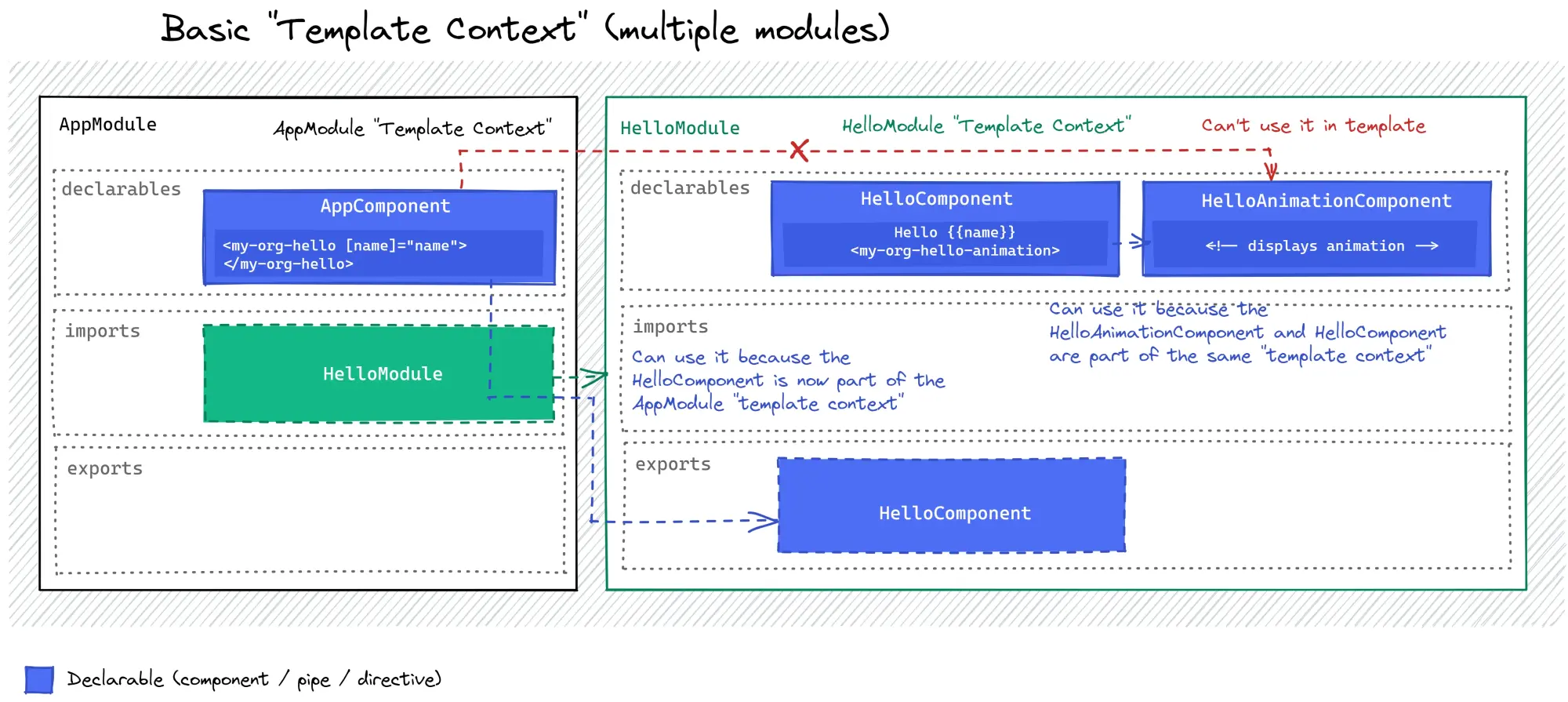

Useful privacy

In our previous example, we have had a HelloComponent which was private to the HelloModule but such privacy was pointless and in fact lead to a compilation error which we had to fix by making the HelloComponent public but this doesn’t mean that the privacy is not useful!

For example, let’s say we have a very specific HelloAnimationComponent which displays waving hand next to the name displayed by the HelloComponent.

Such component will not and should not really be used outside the HelloModule “template context” to prevent undesirable coupling and should therefore stay private.

@NgModule({

declarations: [HelloComponent, HelloAnimationComponent],

imports: [],

exports: [HelloComponent], // <- HelloAnimationComponentis NOT exported, it's private

})

export class HelloModule {}

Built-in modules

Angular comes with modules like CommonModule or RouterModule which bring Angular’s own declarables and make them available to use in our “template contexts”!

As such there is nothing special about them, and they will behave exactly as we have described above…

Let’s illustrate it with an example of the very useful *ngIf directive which will show and hide parts of the component template if the provided condition evaluates to true or false.

We know that the *ngIf directive is part of both declarations: [ ] and exports: [ ] of the CommonModule besides implementation of other common directives and pipes like *ngFor or | json.

@NgModule({

declarations: [

NgIf, // <- declared in exactly one module

// other declarables... (some potentially private only for internal use

],

exports: [

NgIf,

// other declarables which should be public...

],

})

export class CommonModule {} // just an example, part of Angular itself

Importing CommonModule in the AppModule will make all the exported declarables part of that “template context” and make them available for the use in AppComponent template.

But if we had a look in the newly generated Angular app, we would see that there is no CommonModule imported in the AppModule but we could still use directives like *ngIf or *ngFor without error!? Let’s figure out what is going on by exploring a new concept of…

Transitive “template context”

We have seen that we can add a module ( eg HelloModule ) into the imports: [ ] array of the target module ( eg AppModule ) and that will add all the exported declarations: [ ] to the target modules “template context” but what would happen if we exported not just declarables but another modules as well?

Following is a simplified real world scenario which describes exactly that and happens in most Angular apps out there!

@NgModule({

declarations: [AppComponent],

imports: [BrowserModule], // Angular module which sets up app infrastructure

}) // but also something else !

export class AppModule {}

@NgModule({

declarations: [

/* ... */

],

imports: [],

exports: [

CommonModule, // <!-- important ! we're re-exporting a module

// and other local declarables...

],

})

export class BrowserModule {} // just an example, part of Angular itself

@NgModule({

declarations: [

NgIf, // <- declared in exactly one module

// other declarables... (some potentially private only for internal use

],

exports: [

NgIf,

// other declarables which should be public...

],

})

export class CommonModule {} // just an example, part of Angular itself

As we can see, (re)exporting another module ( the CommonModule ) makes all its exported declarables ( eg NgIf ) part of the consumer (AppModule) “template context”!

This means we’re traversing through multiple template context ( 3 in this case, but can be more in practice ) while collecting all the declarables that will be available in the consumer “template context”.

Lazy loading and bundling

The “template context” is relevant in context of optimizing bundle size and lazy loading features of our Angular application!

Let’s think about what is going on in our initial example with AppModule and the HelloModule …

- we have TWO “template contexts”

- the

AppModuleis eagerly loaded because it represents the main entry point of the application is therefore bundled in the main.js (main eager app bundle) - the

HelloModule, even though it’s its own “template context” ( remember privacy… ), is referenced in theimports: [ ]array of the AppModule and will therefore be also bundled in the eager main.js file!

Both of our “template contexts” end up in the same eager lazy loaded bundle but there is a hierarchy in play. The AppModule is the “origin template context” of the main.js bundle and all other “template contexts” which end up in that same main.js bundle have been referenced either directly or transitively though multiple modules!

And guess what, it works exactly the same for lazy loaded @NgModules! Every lazy loaded module is then a new “origin template context” for that bundle and its own separate some-lazy-bundle.js file!

Multiple “template contexts” can be bundle into a single bundle file for both eager and lazy loaded bundles

Real world use-cases and best practices

In practice, we would rarely create a dedicated HelloModule for a separate “template context” in the eager part of our application. It is also common practice to keep AppModule as slim as possible and introduce the CoreModule to take care of all declarables that are needed to implement main layout of the application (header, navigation ,footer, menu …)

These declarables are then exported, so they can be used in the root AppComponent template.

This means that the AppModule ( which imports CoreModule ) is used to define “origin template context” of the eager part of the application.

Every lazy feature has then its own “origin template context” usually defined by the lazy loaded @NgModule ( eg SomeLazyFeatureModule ).

Shared declarables used in multiple template contexts

As we have seen, in practice our application will consist of relatively small eager “template context” brought together by the AppModule and many lazy loaded features and their respective lazy “template contexts”.

Lazy features often need to use common set of base components that are useful in literally all of the features starting with stuff delivered by the Angular own

CommonModulefollowed by things like custom buttons, form fields, and other generic widgets.

This means we have a need to make them part of the lazy “template context” for every single lazy loaded feature of our application and this is usually solved with the creation of SharedModule!

As we have seen, any module can specify:

- declarations – declarables in the local ( current module’s own ) “template context”

- imports – modules which should bring their exported declarables to the local ( current module’s own ) “template context”

- exports – local declarables AND other re-exported modules if some delivered into consumer module “template context”

A typical example would be then SharedModule

@NgModule({

// local template context

declarations: [

// local declarables

MyOrgAnimatedStarComponent, // can use *ngIf (CommonModule is in tpl ctx)

MyOrgRatingComponent, // can use <animated-star> (MyOrgRatingComponent is in tpl ctx)

], // can use <mat-card> (MatCardModule is in tpl ctx)

// CAN'T use <mat-toolbar> (export only)

// brings their exported declarables into local template context

imports: [

CommonModule, // brings *ngIf, *ngFor, ...

MatCardModule, // brings <mat-card>, ...

],

// makes available for consumer template context

export: [

// delivers to consumer "template context"

CommonModule, // consumer can use *ngIf, *ngFor, ...

MatCardModule, // consumer can use <mat-card>, ...

MatToolbarModule, // consumer can use <mat-toolbar>, ...

MyOrgRatingComponent, // consumer can use <my-org-rating>

], // consumer CAN'T use <my-org-animated-start>

// because it's not exported

})

export class SharedModule {} // defines "shared" "template context" (tpl ctx)

With such setup, the transitiveness spans 3 levels from the point of consumer, for example if we have lazy loaded UserModule. Let’s say that the UserModule adds SharedModule to its imports: [ ] array but NOT the CommonModule.

In that case, if a component which is declared in the UserModule ( for example UserItemComponent ) uses the *ngFor directive in its template the way it gets follows these steps ( CTX stands for “template context”) :

- CTX 1 |

UserItemComponentuses*ngForin its template - CTX 1 |

UserItemComponentis a part of thedeclarations: [ ]array of theUserModuleand hence theUserModule“template context” ( lazy loaded ) - CTX 1 |

UserModulehasSharedModulein itsimports: [ ]array - CTX 2 |

SharedModulehasCommonModulein itsexports: [ ]array - CTX 3 |

CommonModulehasNgForin itsexports: [ ]array - CTX 3 |

CommonModulehasNgForin itsdeclarations: [ ]array so theNgForbelongs toCommonModule( can be declared only in a single module ) and the only way to consume it is by importingCommonModule

As we can see, in this example we’re traversing 3 “template contexts” while constructing the template context for the lazy loaded UserModule and determining what can be used in the template of the UserItemComponent.

Stand-alone components approach

Let’s explore exactly the same example but using Angular SACs instead of @NgModules.

@Component({

standalone: true, // <-mark component as standalone

selector: 'my-org-root',

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

}

Using a standalone

AppComponentmeans we do NOT need to useAppModuleand the application will be bootstrapped directly usingboostrapApplication(AppComponent)instead!

Such a solution would again fail with an error similar to the earlier errors about the my-org-hello not being part of the same “template context” ( but this time it’s the component imports instead of module ).

Do you enjoy the theme of the code preview? Explore our brand new theme plugin

@Component({

standalone: true,

selector: 'my-org-root',

imports: [HelloComponent], // <-import another SAC

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

}

The fix was to import the missing HelloComponent ( which is now standalone component ) and adding it to the imports: [ ] array of the parent stand-alone component which is now responsible for managing its own “template context” because there are no @NgModuless involved.

As we can see, the NgModules and Stand-alone components are two ways of achieving the same as they both share the same responsibility of defining and managing the “template context” for the involved components!

This is the main reason for the bold initial statement that the “template context” is “The Most Important Thing You Need To Understand About Angular” because it describes how Angular works at its utmost core, and it isn’t going to change in the foreseeable future!

SACs are similar to SCAMs

Consider following example…

// SCAM

@Component({

/* ... */

})

export class HelloComponent {}

@NgModule({

declarations: [HelloComponent], // always only one declarable, the component

exports: [HelloComponent], // always only one declarable, the component

imports: [

CommonModule,

// other standard modules...

// other SCAMs...

],

})

export class HelloModule {}

// is the same as

// SAC

@Component({

/* ... */

imports: [

// other SACs...

// other standard modules...

// other SCAMs...

],

// with SACs we CAN'T specify exports: [] which fits the use case

// because we should only export the component itself

// and the component is exported implicitly (less verbose)

})

export class HelloComponent {}

Now let’s make that simple example more complex by using *ngIf directive to show or hide hello message based on user interaction.

@Component({

standalone: true,

selector: 'my-org-root',

imports: [HelloComponent], // <-import another SAC

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name" *ngIf="showHello"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

showHello = true;

}

In such case we would again get an error because we’re trying to use a directive ( declarable ) which is NOT part of our “template context”.

NG8103: The `*ngIf` directive was used in the template, but neither the `NgIf` directive nor the `CommonModule` was imported. Please make sure that either the `NgIf` directive or the `CommonModule` is included in the `@Component.imports` array of this component

Will have to import CommonModule in the imports: [ ] array of the SAC component itself because we now don’t have parent @NgModule anymore.

@Component({

standalone: true,

selector: 'my-org-root',

imports: [HelloComponent, CommonModule], // <-import CommonModule

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name" *ngIf="showHello"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

showHello = true;

}

This works as expected because the SAC manages the “template context” for itself and importing the CommonModule makes it part of that “template context” and hence the *ngIf also becomes part of the same “template context” and can be therefore be used in the template!

As it turns out, besides exporting the NgIf directive with the help of CommonModule, Angular also exposes it as a stand-alone directive ( SAD ?! 🤔😅 ) which can be consumed directly! Because of this we will be able to add it to the imports: [ ] array of the parent SAC component.

@Component({

standalone: true,

selector: 'my-org-root',

imports: [HelloComponent, NgIf], // <-import NgIf (SAC)

template: ` <my-org-hello [name]="name" *ngIf="showHello"></my-org-hello> `,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Tomas Trajan';

showHello = true;

}

Both of the above approaches work exactly the same, only difference being that using CommonModule instead of NgIf leads to a slightly larger bundle size as the CommonModule brings implementation of other common directives and pipes like *ngIf or | keyvalue.

On the other hand, most nontrivial applications are going to use most of them so this becomes our first official encounter which exposes trade-off between:

- developer experience removing the need to manage long fully granular list of dependencies manually by using entities which group them together like

CommonModule - smallest possible bundle size managing long fully granular list of dependencies which means more work for developers but smallest bundle size possible

The SACs do NOT support multi level transitive approach to “template context” when used on their own as they lack capability to specify exports: [ ] array and because of that every SAC has to fully define its own template context*

- (*) of course SACs and

@NgModuleapproach can be easily mixed and matched and adding@NgModules to the mix would bring back the capability of multi level transitiveness

Now that was an intense ride! My best guess is that you were probably already familiar with many aspects of the template context beforehand, but I hope you could find at least 1 or 2 new things anyway! 😅

Useful questions

Now we’re going to go through a couple of useful questions you can ask yourself when working on your application!

- is current “template context” eager or lazy?

- what is available in my current context? ( do I have everything I need, do I have too much? (perf) )

- is a declarable available directly or transitively?

- is declarable made available once or through multiple imports simultaneously? ( has impact when trying to remove it from context when unnecessary )

- what won’t be available anymore if remove given import?

- which declarables are used in multiple ( many ) lazy loaded “template contexts”? ( candidates for

SharedModule) - do I want to manage my “template contexts” as granular as possible ? ( use SAC ) or do I prefer some grouping and better DX? (

SharedModule)

Wrap up

I hope You enjoyed learning about the “template context” mental model aka “The Most Important Thing You Need To Understand About Angular” 😉

Let me know in comments if you would like to expand this topic to cover things like how this applies to Angular libraries and more real world examples of managing “template context” in large Angular applications!

Please support this guide by sharing it with your colleagues who could find these tips useful🙏.

Also, don’t hesitate to ping me if you have any questions using the article responses or Twitter DMs @tomastrajan

And never forget, future is bright

Obviously the bright Future! (📸 by Marc Zimmer )